Real-World Evidence Analysis: Impact of Antibacterial Resistance on In-Hospital Mortality

This document presents a methodological reimplementation of a published study on the burden of antibacterial resistance on mortality in Marseille (AP-HM, 2014–2018).

No original patient-level or confidential hospital data are used here.

All analyses are based on simulated or anonymized / reconstructed datasets that replicate the patterns and methodology described in the original publication.

The aim is to demonstrate Real-World Evidence (RWE) methods, data engineering, and statistical modeling for my professional portfolio.

The results presented here must not be interpreted as official AP-HM results.

Overview

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a major challenge in clinical practice, and real-world data provide valuable insights into its true clinical burden beyond controlled trials.

This project reimplements, using simulated data, the analytical framework of a real-world evidence (RWE) study that assessed the impact of antibacterial resistance on hospital mortality across four university hospitals in Marseille, France

Study type: Retrospective, multi-center, observational real-world evidence study

Data source (conceptual): Routine blood culture results (MARSS surveillance system) linked with hospital mortality

Population: All patients with at least one blood culture performed in AP-HM during the study period

Primary outcome: In-hospital mortality

Key exposures

- Resistance to key antibiotics for top bacterial species

- Difficult-to-treat resistance (DTR) phenotype

- Hospital-acquired infection, ICU admission, and other clinical factors

Research Question

What is the real-world burden of antibacterial resistance on in-hospital mortality among patients with blood cultures in a large French university hospital system?

Methods

Study Design

Retrospective observational study based on routine laboratory and hospital data.

Patients with at least one blood culture were followed until hospital discharge or death.

Setting

- Four University Hospitals of Marseille (AP-HM), France

- Study period: February 2014 – February 2018.

Population & Variables

All patients with ≥1 blood culture (positive or negative).

Analyses focused on positive cultures involving the 10 most frequent bacterial species in the deceased group, plus Acinetobacter baumannii.

Variables:

- Outcome: In-hospital death (yes/no)

- Key exposures:

Resistance to key antibiotics (e.g., ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, imipenem, amikacin)

DTR phenotype: resistant to all first-line agents (Kadri et al. definition)

- Covariates: Age (>60 vs ≤60), sex, hospital-acquired infection (>48h after admission), ICU admission, length of stay (>14 days), bacterial species.

Statistical Approach

Descriptive analyses summarized bacterial species distributions and resistance rates. Logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for in-hospital mortality associated with key exposures, including hospital-acquired infections, ICU admission, bacterial species, and DTR phenotype.

All results are based on synthetic / simulated data emulating published patterns.

Abbreviations

AMR: antimicrobial resistance;

RWD: real-world data;

RWE: real-world evidence;

DTR: difficult-to-treat resistance;

ICU: intensive care unit;

AST: antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Results

Among all patients with blood cultures, those with positive results had nearly twice the mortality of those with negative cultures.

The most common bacteria in both groups were Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Resistance to ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, and imipenem was more prevalent among deceased patients (Table 1 Table 2 Table 3).

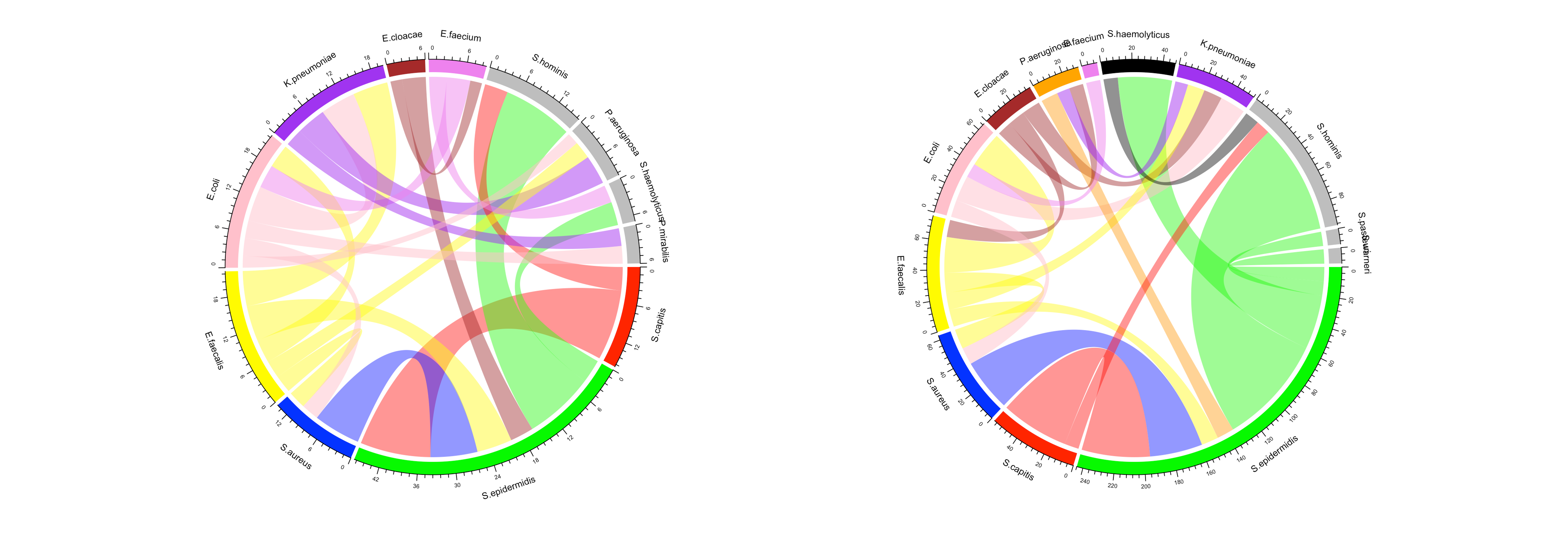

Polymicrobial bloodstream infections were more frequent among deceased patients (9.4%) than survivors (6.8%; p = 0.004). Excluding coagulase-negative staphylococci, E. coli and K. pneumoniae predominated among the deceased, while E. coli and S. aureus were most frequent among survivors. Gram-negative bacteria accounted for a larger share of co-infections in the death group (72.2%) than in controls (48.6%) (Figure 1).

Hospital-acquired infection (OR≈1.5), ICU admission (OR≈2.9), and P. aeruginosa or E. faecium infection (OR≈1.6–1.9) were independent mortality risk factors (Table 4).

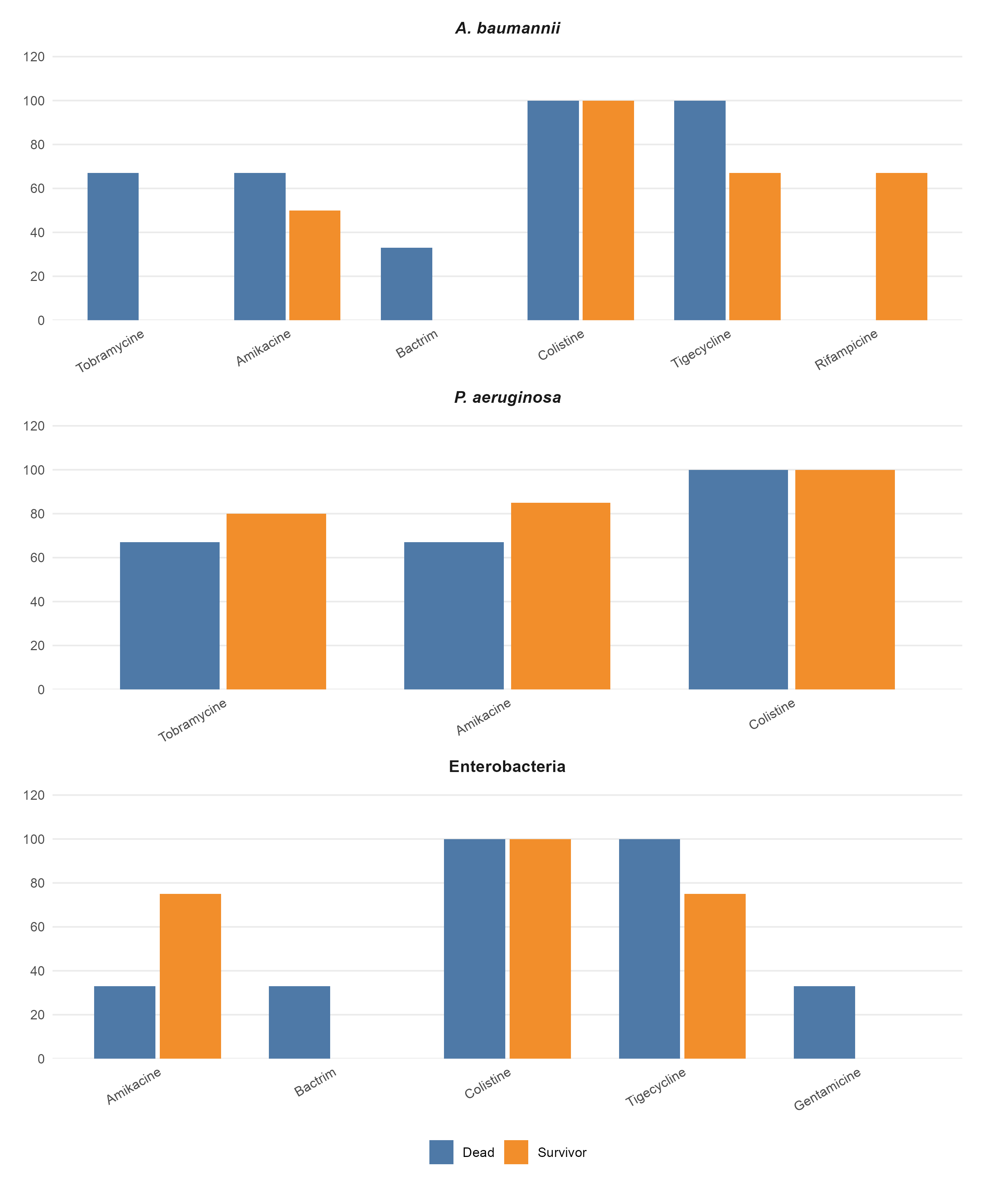

The DTR phenotype was rare (≈0.3%) but significantly more frequent among deceased patients (Figure 2).

| Antibiotic | Resistance | Deaths | Survivors | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | R | 172 | 1,175 | 0.20 |

| S | 93 | 742 | ||

| AST | 265 | 1,917 | ||

| Number of patients | 268 | 1,930 | ||

| Amoxicillin–Clavulanic acid | R | 156 | 1,008 | 0.08 |

| S | 112 | 916 | ||

| AST | 268 | 1,924 | ||

| Number of patients | 268 | 1,930 |

| Antibiotic | Resistance | Deaths | Survivors | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone | R | 64 | 274 | <0.0001 |

| S | 203 | 1,654 | ||

| AST | 267 | 1,928 | ||

| Number of patients | 268 | 1,930 | ||

| Imipenem | R | 1 | 1 | 0.40 |

| S | 267 | 1,911 | ||

| AST | 268 | 1,929 | ||

| Number of patients | 268 | 1,930 |

| Antibiotic | Resistance | Deaths | Survivors | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | R | 84 | 421 | 0.007 |

| S | 184 | 1,506 | ||

| AST | 268 | 1,927 | ||

| Number of patients | 268 | 1,930 | ||

| Amikacin | R | 9 | 45 | 0.44 |

| S | 259 | 1,878 | ||

| AST | 268 | 1,924 | ||

| Number of patients | 268 | 1,930 |

| Risk factors | aOR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Patient & care factors | ||

| Age (>60 years) | 2.2 (1.9–2.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Gender (Male) | 1.13 (0.97–1.6) | 0.08 |

| Long hospital stay (>14 days) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 0.05 |

| Hospital-acquired infections | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Hospitalization Unit | ||

| Emergency Unit | 1 (reference) | — |

| Surgery Unit | 0.35 (0.26–0.46) | < 0.0001 |

| Medical Unit | 0.73 (0.59–1.3) | 0.07 |

| Intensive Care Unit | 2.9 (2.4–3.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Bacterial species | ||

| S. epidermidis | 0.8 (0.7–0.96) | 0.02 |

| K. pneumoniae | 1.2 (0.97–1.6) | 0.07 |

| P. aeruginosa | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 0.01 |

| S. hominis | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.15 |

| E. faecalis | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 0.4 |

| E. faecium | 1.9 (1.3–2.9) | 0.001 |

Positive blood cultures nearly doubled in-hospital mortality.

ICU admission, hospital-acquired infection, and infections by P. aeruginosa / E. faecium remained independently associated with death.

DTR phenotypes were rare but enriched among deceased patients.

Discussion

This analysis highlights the value of real-world data in quantifying the clinical burden of antimicrobial resistance and identifying high-risk patient groups. Integrating such insights into antimicrobial stewardship and hospital surveillance systems can guide targeted interventions and resource allocation.

RWE Value

Demonstrates secondary use of hospital RWD for public health.

Replicates real-world associations outside clinical trial settings.

Highlights integration potential with HEOR studies (e.g., cost of AMR-related deaths).

Perspective

Future applications of this analytical framework could include cost-effectiveness modeling, regional comparisons, and integration with national AMR surveillance systems.

Limitations

Retrospective observational design.

Possible misclassification of infection source.

Analyses conducted on synthetic / anonymized data, not actual hospital data.

Ethics and Data Governance

This portfolio project complies with ethical standards for the use of health data:

No identifiable or proprietary hospital data were accessed.

All datasets were synthetic, simulated, or anonymized.

The work is for educational and methodological purposes only.

No institutional review board (IRB) approval was required for this reimplementation.

All analytical steps comply with the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles for responsible secondary use of health data.

Reproducibility and Skills Demonstrated

Analytical skills illustrated in this project:

Real-world data curation and cleaning (R, tidyverse, dplyr, lubridate).

Epidemiological study design and variable definition.

Logistic regression modeling of clinical outcomes.

Data visualization (R/ggplot2) and RWE storytelling.

Ethical and regulatory awareness in secondary data use.

Ousmane Diallo, MPH-PhD – Biostatistician, Data Scientist & Epidemiologist based in Chicago, Illinois, USA. Specializing in SAS programming, CDISC standards, and real-world evidence for clinical research.

Back to top